The Museum of Printing and graphic communication, a team-player in the graphic arts

Created by the master-printer Maurice Audin (1895–1975), son of the learned printer-publisher Marius Audin (1872–1951) and brother of Amable, the founder of the Lyon Archaeological Museum, the Museum of Printing opened in 1964 in the former Hôtel de la Couronne, a Renaissance building which was Lyon's first city hall between 1604 and 1655. Henri-Jean Martin, at that time director of Lyon city libraries and later founder of the French school of the history of books, and André Jammes, a Parisian bookseller, took part in the organisation and acquisition of the permanent collection. The richness of the Museum's heritage material made it one of the leaders in the field in Europe. Today, the Museum is recognised nationally and internationally in the world of graphic arts, making a major contribution via some exceptional temporary

exhibitions : Les Didot, 1988 ; Le Romain du Roi, 2002 ; Chromolithographie, 2005 ; Art pour tous, 2011 ; Transatlantiques, 2013… Regular exchanges take place with Great Britain and other European countries, Canada, the United States, South Korea ...

The Museum is a founder member of the 'Association of European Printing Museums, a grouping of the leading European museums, heritage institutions and workshops; the Museum's director from 2002 to 2015, Alan Marshall, is the president of AEPM since 2012. Between 2007 and 2013 the Museum has seen a major increase in visitor numbers and has attracted a growing number of young people.

An enlarged collection

The Museum celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2014 with a major renovation of the permanent collection and a new name, Museum of printing and graphic communication, reflecting its involvement in the world of today. In the fifty years of the Museum's existence the graphic industries have undergone rapid change from traditional techniques to those of the digital age. The Museum's collections reflect this evolution and have been considerably enlarged.

Rubbing shoulders with rare books and prints, printed matter of all kinds has made a massive entry, from bus tickets to Tour de France caps, from advertisements for “Vache qui rit” dairy products to railway timetables, from free newspapers to record sleeves from the 1960s and comics, not to mention objects which bear witness to the digital revolution such as punched tapes and cards, memory units, computer programs, photocomposition machines and digital type-faces...

In this enlarged collection considerable space in the Museum is devoted to printed and other objects resulting from the teeming graphic creativity of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Museum of printing and graphic communication also offers throughout the year and to people of all ages a programme of visits and workshops linked to the permanent collection and to temporary exhibitions.

Intertype composing machine - 2nd floor

1st floor

2nd floor

2nd floor

Permanent exhibition

The beginnings of printing: reproduction of texts and images

The displays in the first room relate developments before, and leading to, the invention of printing. In the libraries of the Ancient World, books took the form of scrolls, which gradually gave way to the codex, folded rectangular sheets bound together to form a book. This development gave rise to a major innovation: the page.

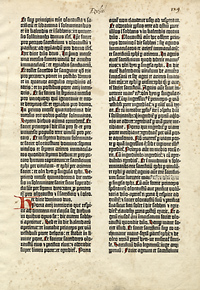

In the mid-15th century, letterpress printing was perfected in Mainz in Germany. The name of Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg is forever associated with this technical innovation, which was to have a profound impact on the future of European civilization, radically transforming the way knowledge and ideas are communicated. One of the most historic and rare objects in this room is a leaf of Gutenberg's 42-line Bible, the first book printed in Europe.

Gutenberg's method of printing is based on the ease with which large numbers of types can be cast by hand and composed to produce a perfectly flat surface which be inked and printed using a mechanical system – the printing press – to transfer the ink onto the paper. Once Gutenberg's invention had proved itself, its rise was irresistible: by the end of the 15th century more than 250 towns in Europe had print shops.

Gutenberg's 42 line bible

The beginnings of printing: reproduction of texts and images

The displays in the first room relate developments before, and leading to, the invention of printing. In the libraries of the Ancient World, books took the form of scrolls, which gradually gave way to the codex, folded rectangular sheets bound together to form a book. This development gave rise to a major innovation: the page.

In the mid-15th century, letterpress printing was perfected in Mainz in Germany. The name of Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg is forever associated with this technical innovation, which was to have a profound impact on the future of European civilization, radically transforming the way knowledge and ideas are communicated. One of the most historic and rare objects in this room is a leaf of Gutenberg's 42-line Bible, the first book printed in Europe.

Gutenberg's method of printing is based on the ease with which large numbers of types can be cast by hand and composed to produce a perfectly flat surface which be inked and printed using a mechanical system – the printing press – to transfer the ink onto the paper. Once Gutenberg's invention had proved itself, its rise was irresistible: by the end of the 15th century more than 250 towns in Europe had print shops.

Gutenberg's 42 line bible

Printing and the Renaissance in Lyon

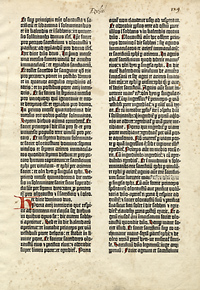

In collaboration with the illustrator Bernard Salomon, the printer Jean de Tournes produced works of exceptional quality in Lyon during this period. With the expansion of printing, a new, resolutely international market for books came into being in Europe. Starting at the end of the 15th century, the printed book progressively abandoned the conventions of manuscript form. The content too evolved.

Printer-booksellers added new kinds of works to their range, often by living authors, and played a leading role in spreading the ideas of the Renaissance and the Reformation.

Historical quatrains of the Bible (1553) by Claude Paradin

In collaboration with the illustrator Bernard Salomon, the printer Jean de Tournes produced works of exceptional quality in Lyon during this period. With the expansion of printing, a new, resolutely international market for books came into being in Europe. Starting at the end of the 15th century, the printed book progressively abandoned the conventions of manuscript form. The content too evolved.

Printer-booksellers added new kinds of works to their range, often by living authors, and played a leading role in spreading the ideas of the Renaissance and the Reformation.

Historical quatrains of the Bible (1553) by Claude Paradin

Reformation and Counter-Reformation

In the early 16th century, the Catholic Church was all powerful, but the vast edifice was beginning to show cracks.

The Protestant Reformation took several forms – Lutheranism, Calvinism, Anabaptism and others. They all rejected the Pope's authority, devotion to the Saints and the Virgin Mary, and the doctrine of purgatory. The reformers translated the Bible and taught people to read.

Printers had to take sides, and if they were not careful, risked being burnt at the stake. In France, the censorship introduced by Francois I in 1521 controlled printed production. In 1558 the first Roman Index of banned books was drawn up by the Catholic Church.

The Spanish Inquisition also strictly controlled the sale and circulation of books.

On the Protestant side also there was no freedom to sell books or read what one liked. In the 16th century trials for witchcraft increased significantly in the small German states, Great Britain and the American colonies.

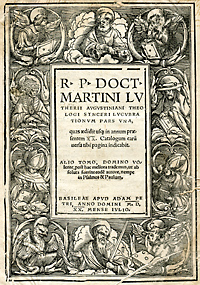

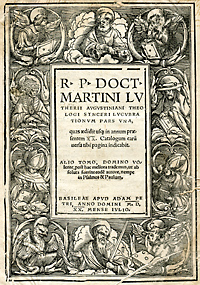

Title page of a 1520 Basle edition of Martin Luther’s writings

In the early 16th century, the Catholic Church was all powerful, but the vast edifice was beginning to show cracks.

The Protestant Reformation took several forms – Lutheranism, Calvinism, Anabaptism and others. They all rejected the Pope's authority, devotion to the Saints and the Virgin Mary, and the doctrine of purgatory. The reformers translated the Bible and taught people to read.

Printers had to take sides, and if they were not careful, risked being burnt at the stake. In France, the censorship introduced by Francois I in 1521 controlled printed production. In 1558 the first Roman Index of banned books was drawn up by the Catholic Church.

The Spanish Inquisition also strictly controlled the sale and circulation of books.

On the Protestant side also there was no freedom to sell books or read what one liked. In the 16th century trials for witchcraft increased significantly in the small German states, Great Britain and the American colonies.

Title page of a 1520 Basle edition of Martin Luther’s writings

Prints

The term ‘print' is generally used to describe a document which has been designed and produced as a single sheet. The relative ease with which prints could be produced and the immense variety of their uses contributed greatly to their success over the centuries.

Improvements in printing techniques made it possible to produce ever more detailed and refined images. The earliest prints were produced from woodcuts; copperplate engraving developed in the 15th century. As of the Renaissance, prints were used to reproduce paintings, thus providing artists with a means of making their works known to a wider audience who could more easily afford a print than a painting.

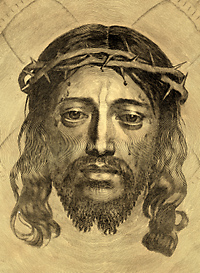

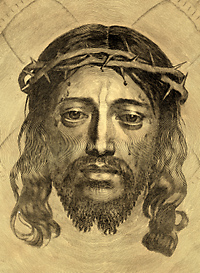

The development of printing in the 15th and 16th centuries, reinforced in the 17th century by the emergence of print-selling as a recognized profession, offered a means of recounting the world in images, a situation which was. Two masterpieces in the second room , "La Sainte-Face" (1642) by Claude Mellan, engraved in one continuous stroke and "The last supper" (1523) by the great Albrecht Dürer.

La Sainte Face / Claude Mellan, 1642.

The term ‘print' is generally used to describe a document which has been designed and produced as a single sheet. The relative ease with which prints could be produced and the immense variety of their uses contributed greatly to their success over the centuries.

Improvements in printing techniques made it possible to produce ever more detailed and refined images. The earliest prints were produced from woodcuts; copperplate engraving developed in the 15th century. As of the Renaissance, prints were used to reproduce paintings, thus providing artists with a means of making their works known to a wider audience who could more easily afford a print than a painting.

The development of printing in the 15th and 16th centuries, reinforced in the 17th century by the emergence of print-selling as a recognized profession, offered a means of recounting the world in images, a situation which was. Two masterpieces in the second room , "La Sainte-Face" (1642) by Claude Mellan, engraved in one continuous stroke and "The last supper" (1523) by the great Albrecht Dürer.

La Sainte Face / Claude Mellan, 1642.

Printing under the Ancien Régime

In the 17th century the French book trade was open to Europe and its colonies and showed considerable dynamism despite the fact that its techniques and organisation (often family-based) had hardly changed over the previous two centuries. Printing was, however, becoming increasingly diversified in terms of content, formats, design and illustration.

Printing was strictly controlled. State and religious censorship was omnipresent, but despite the penalties which could be incurred for breach of the regulations, there was a remarkably vigorous trade in forbidden books published under false addresses, as well as of unauthorised editions of titles supposedly protected by privilege.

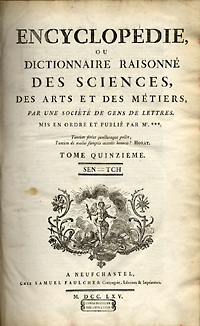

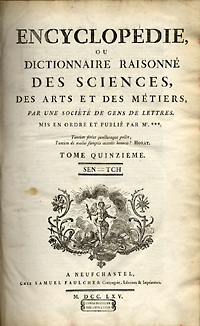

One of the most famous French publications is the 18th century Encyclopédie. Here you will also find printed items with a much shorter intended life – ephemera.

Diderot and D’Alembert's Encyclopedia / Paris, 1751–1776.

In the 17th century the French book trade was open to Europe and its colonies and showed considerable dynamism despite the fact that its techniques and organisation (often family-based) had hardly changed over the previous two centuries. Printing was, however, becoming increasingly diversified in terms of content, formats, design and illustration.

Printing was strictly controlled. State and religious censorship was omnipresent, but despite the penalties which could be incurred for breach of the regulations, there was a remarkably vigorous trade in forbidden books published under false addresses, as well as of unauthorised editions of titles supposedly protected by privilege.

One of the most famous French publications is the 18th century Encyclopédie. Here you will also find printed items with a much shorter intended life – ephemera.

Diderot and D’Alembert's Encyclopedia / Paris, 1751–1776.

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution started in Great Britain in the late 18th century with a series of technical innovations. Systems of transport – railways, rivers and the sea – and a growing telegraph network underpinned national and international expansion of economic activity.

The world of printing also experienced major changes, mainly to do with mechanisation. The invention of lithography and later of photography boosted the reproduction of images, and posters invaded the street scene. Publishing became industrialised and cheap newspapers sprang up, profiting from the steadily increasing, hard-won liberty of the press. In this increasingly complex society, information was conveyed via a myriad of administrative and commercial documents: forms, technical instructions, advertisements, illustrated posters, labels, packaging...

A key invention from this period is lithography, which is explained in a video in this room. The superb poster for the newspaper Le Figaro by Jules Chéret dates from 1895.

Jules Cheret's typical poster style / Paris, 1896.

The Industrial Revolution started in Great Britain in the late 18th century with a series of technical innovations. Systems of transport – railways, rivers and the sea – and a growing telegraph network underpinned national and international expansion of economic activity.

The world of printing also experienced major changes, mainly to do with mechanisation. The invention of lithography and later of photography boosted the reproduction of images, and posters invaded the street scene. Publishing became industrialised and cheap newspapers sprang up, profiting from the steadily increasing, hard-won liberty of the press. In this increasingly complex society, information was conveyed via a myriad of administrative and commercial documents: forms, technical instructions, advertisements, illustrated posters, labels, packaging...

A key invention from this period is lithography, which is explained in a video in this room. The superb poster for the newspaper Le Figaro by Jules Chéret dates from 1895.

Jules Cheret's typical poster style / Paris, 1896.

The new document economy

During the nineteenth century, many new uses were found for printing and styles developed accordingly. In administration, books gave way to documents, ‘writing' to ‘information'.

Texts were no longer read systematically from start to finish. Certain kinds of documents were presented in a structured manner in order to guide readers to the information they were looking for, and this required new typographic techniques: lists, tables, bold and italic type, indents, boxes and the like.

As the document replaced the book, so the pen gave way to the typewriter which became one of the most widespread tools of the modern world.

Hammond typewriter (early 20th century).

During the nineteenth century, many new uses were found for printing and styles developed accordingly. In administration, books gave way to documents, ‘writing' to ‘information'.

Texts were no longer read systematically from start to finish. Certain kinds of documents were presented in a structured manner in order to guide readers to the information they were looking for, and this required new typographic techniques: lists, tables, bold and italic type, indents, boxes and the like.

As the document replaced the book, so the pen gave way to the typewriter which became one of the most widespread tools of the modern world.

Hammond typewriter (early 20th century).

Photography and printing in colour: images for all

The nineteenth century is the century of the image. From a technical point of view it was a period of intense experimentation. Lithography, developed in the early years of the century, found innumerable

applications : initially used for black and white work, it was later developed for colour printing.

The invention of photography also had a profound impact on printing. In the 1880s, photoengraving processes progressively replaced wood engraving in practically all but a few specialised fields of illustration.

The 19th century also witnessed a spectacular popularisation of printed images which because of their high production costs had been limited to a market of the well-off (the exception being popular prints which were generally of relatively poor quality). Printed images became available to all thanks to new industrially exploitable illustration techniques.

Lots of examples of chromolithography. Of particular interest is a set of proofs in the order in which the seven colours used are printed to produce a wrapper for chocolate.

Advertisement for the famous British bicycle manufacturer Rudge, 1900.

The nineteenth century is the century of the image. From a technical point of view it was a period of intense experimentation. Lithography, developed in the early years of the century, found innumerable

applications : initially used for black and white work, it was later developed for colour printing.

The invention of photography also had a profound impact on printing. In the 1880s, photoengraving processes progressively replaced wood engraving in practically all but a few specialised fields of illustration.

The 19th century also witnessed a spectacular popularisation of printed images which because of their high production costs had been limited to a market of the well-off (the exception being popular prints which were generally of relatively poor quality). Printed images became available to all thanks to new industrially exploitable illustration techniques.

Lots of examples of chromolithography. Of particular interest is a set of proofs in the order in which the seven colours used are printed to produce a wrapper for chocolate.

Advertisement for the famous British bicycle manufacturer Rudge, 1900.

The graphic revolution

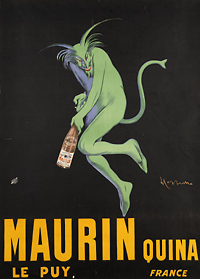

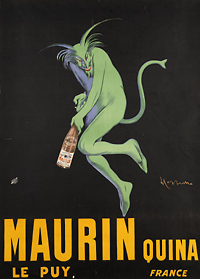

A new phase of the industrial revolution began in the 1880s, in which communications played a key role in the organisation of an increasingly complex society, with spectacular growth in the quantity of information and the speed of its dissemination, mainly in the form of printed material. Printing and publishing became industrialised. The newspaper press, the first of the mass media, attained its hour of glory.

Within the graphic industries progress in colour printing, the development of new techniques based on photography, and the rising importance of advertising resulted in a veritable revolution. From now on the informative role of the printed word was reinforced by the force of persuasion of the printed image.

Industrial capitalism became dependent on marketing, advertising and the promotion of ‘brand image', and graphic artists came to play a central part in the development of new styles of communication.

Perhaps the most striking poster is the one by Capiello in 1906 for Maurin Quina.

Among the objects in the display-cases, the packaging for a certain brand of cheese wil probably be familiar to French visitors – and maybe to others.

In the inter-war period in London, the transport authority commissiones posters from leading artists.

Maurin Quina / Leonetto Capiello. Le Puy, 1906.

A new phase of the industrial revolution began in the 1880s, in which communications played a key role in the organisation of an increasingly complex society, with spectacular growth in the quantity of information and the speed of its dissemination, mainly in the form of printed material. Printing and publishing became industrialised. The newspaper press, the first of the mass media, attained its hour of glory.

Within the graphic industries progress in colour printing, the development of new techniques based on photography, and the rising importance of advertising resulted in a veritable revolution. From now on the informative role of the printed word was reinforced by the force of persuasion of the printed image.

Industrial capitalism became dependent on marketing, advertising and the promotion of ‘brand image', and graphic artists came to play a central part in the development of new styles of communication.

Perhaps the most striking poster is the one by Capiello in 1906 for Maurin Quina.

Among the objects in the display-cases, the packaging for a certain brand of cheese wil probably be familiar to French visitors – and maybe to others.

In the inter-war period in London, the transport authority commissiones posters from leading artists.

Maurin Quina / Leonetto Capiello. Le Puy, 1906.

The golden age of the newspaper

The turn of the twentieth century was the golden age of the newspaper. In France the press became a major industry, helped by technical progress and by the more liberal politics of the Third Republic.

Newspapers, which had now become commonplace, started to diversify into different social, geographic and ideological markets. Mass circulation papers became less political to attract a wider readership.

Journalism as a career attracted more people. The press played an increasing role in a rapidly changing society. But economically, it was a business like any other and had to pay its way. For many newspapers it was as important to sell its readers to advertisers as it was to sell information to its readers.

Up until the 1970s newspapers were produced on thousands of composing machines of this kind. Here we have an Intertype from the 1930s.

Paris Match, 4 juin 1960.

The turn of the twentieth century was the golden age of the newspaper. In France the press became a major industry, helped by technical progress and by the more liberal politics of the Third Republic.

Newspapers, which had now become commonplace, started to diversify into different social, geographic and ideological markets. Mass circulation papers became less political to attract a wider readership.

Journalism as a career attracted more people. The press played an increasing role in a rapidly changing society. But economically, it was a business like any other and had to pay its way. For many newspapers it was as important to sell its readers to advertisers as it was to sell information to its readers.

Up until the 1970s newspapers were produced on thousands of composing machines of this kind. Here we have an Intertype from the 1930s.

Paris Match, 4 juin 1960.

The information society

During the second half of the 20th century graphic communication underwent a radical change, as three previously separate areas of economic activity – printing, the production of administrative documents, and information technology – came together.

From the time of Gutenberg up until the late 19th century printers had held the monopoly of the reproduction in quantity of texts and images. This situation changed with the development of cheaper techniques of composition and printing which facilitated the production of documents of reasonable typographical quality.

The arrival of computers after the Second World War changed the rules of the game. Thanks to computers, printers could tap directly into administrative and commercial databases, cutting out the intermediate, specialised stage of typesetting.

The coming together of printing, office work and information technology was crowned in 1984 with the launch of the Apple Macintosh, marking the starting-point of desk-top publishing (DTP). Today the simplest personal computer provides graphic tools far more powerful and productive than the specialised machines and systems used by the print industry before the digital revolution.

Macintosh Classic, circa 1990.

During the second half of the 20th century graphic communication underwent a radical change, as three previously separate areas of economic activity – printing, the production of administrative documents, and information technology – came together.

From the time of Gutenberg up until the late 19th century printers had held the monopoly of the reproduction in quantity of texts and images. This situation changed with the development of cheaper techniques of composition and printing which facilitated the production of documents of reasonable typographical quality.

The arrival of computers after the Second World War changed the rules of the game. Thanks to computers, printers could tap directly into administrative and commercial databases, cutting out the intermediate, specialised stage of typesetting.

The coming together of printing, office work and information technology was crowned in 1984 with the launch of the Apple Macintosh, marking the starting-point of desk-top publishing (DTP). Today the simplest personal computer provides graphic tools far more powerful and productive than the specialised machines and systems used by the print industry before the digital revolution.

Macintosh Classic, circa 1990.

The Lumitype, invented in Lyon

In the 1940s, Lyon found itself at the heart of an innovation which would drive printing, and indeed graphic technique, in a new direction. The adventure began in 1944 when two French engineers, Rene Higonnet (1904-83) and Louis Moyroud (1914-2010) lodged their first patents for a photocomposition machine on behalf of LMT, the company for which they worked at 31 place Bellecour. The machine was the Lumitype, the first “second generation” photocomposition machine, which they had designed ; it would be ten years before a commercial version was produced.

The system involves a combination of ultra-fast photography and binary calculation. The heart of the machine is a disc, turning at eight revolutions per second, on which eight character-sets are stocked concentrically, in the form of negative images. Text is input via a simple keyboard like that of an electric typewriter. The image of each letter is flashed onto a film covered with a layer of photo-sensitive emulsion. An optical system determines the size of characters and positions them on the photographic material while an electro-magnetic (later electronic) binary system memorises the current line of text.

The significance of this machine is that it de-materialises type, a step in a development which broadened during the following years with integration to offset printing, then computerisation of composition and eventually DTP (desktop publishing). Lead had given way to light. The idea of founding thousands of types and assembling them to form a text now belongs to the past.

In 1957, the printers Berger-Levrault in Nancy were the first in France to instal the Lumitype, publishing an edition of Beaumarchais' The marriage of Figaro. In Lyon, the history of this invention is kept alive particularly by the acquisition by the Museum of printing and graphic communication of the professional papers of Higonnet and Moyroud, an exceptional body of material in this field.

Lumitype-Photon : photographic unit.

In the 1940s, Lyon found itself at the heart of an innovation which would drive printing, and indeed graphic technique, in a new direction. The adventure began in 1944 when two French engineers, Rene Higonnet (1904-83) and Louis Moyroud (1914-2010) lodged their first patents for a photocomposition machine on behalf of LMT, the company for which they worked at 31 place Bellecour. The machine was the Lumitype, the first “second generation” photocomposition machine, which they had designed ; it would be ten years before a commercial version was produced.

The system involves a combination of ultra-fast photography and binary calculation. The heart of the machine is a disc, turning at eight revolutions per second, on which eight character-sets are stocked concentrically, in the form of negative images. Text is input via a simple keyboard like that of an electric typewriter. The image of each letter is flashed onto a film covered with a layer of photo-sensitive emulsion. An optical system determines the size of characters and positions them on the photographic material while an electro-magnetic (later electronic) binary system memorises the current line of text.

The significance of this machine is that it de-materialises type, a step in a development which broadened during the following years with integration to offset printing, then computerisation of composition and eventually DTP (desktop publishing). Lead had given way to light. The idea of founding thousands of types and assembling them to form a text now belongs to the past.

In 1957, the printers Berger-Levrault in Nancy were the first in France to instal the Lumitype, publishing an edition of Beaumarchais' The marriage of Figaro. In Lyon, the history of this invention is kept alive particularly by the acquisition by the Museum of printing and graphic communication of the professional papers of Higonnet and Moyroud, an exceptional body of material in this field.

Lumitype-Photon : photographic unit.

We are all printers now

1968 marked a turning-point in social history, especially in France, and do-it-yourself poster production had arrived to publicise the subversives' cause.

From the time of Gutenberg until the 1960s, printing continued was a closed shop based on expensive machinery and a highly skilled workforce.

During the first half of the 20th century the print trade's de facto monopoly was challenged to some extent by the spread of cheaper methods of composing and printing business documents.

But it was during in the second half of the 20th century that print production really became democratised. This move started in the offices of large companies and government departments, for whom the distribution of information on an ever-widening scale had become a major challenge.

Graphic production also opened its doors in the 1960s to the worlds of political unrest and the counter-culture which challenged the modes of production and the established principles of graphic design used in the traditional media.

Xerox photocopier 660.

1968 marked a turning-point in social history, especially in France, and do-it-yourself poster production had arrived to publicise the subversives' cause.

From the time of Gutenberg until the 1960s, printing continued was a closed shop based on expensive machinery and a highly skilled workforce.

During the first half of the 20th century the print trade's de facto monopoly was challenged to some extent by the spread of cheaper methods of composing and printing business documents.

But it was during in the second half of the 20th century that print production really became democratised. This move started in the offices of large companies and government departments, for whom the distribution of information on an ever-widening scale had become a major challenge.

Graphic production also opened its doors in the 1960s to the worlds of political unrest and the counter-culture which challenged the modes of production and the established principles of graphic design used in the traditional media.

Xerox photocopier 660.

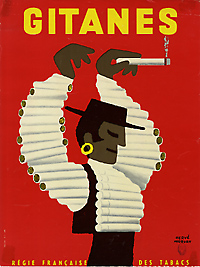

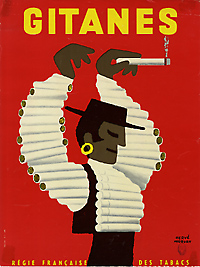

The image reigns supreme

One of the foremost 20th century French graphic artists was Roger Excoffon. One example of his work is the highly evocative poster which he designed for Air France in 1964.

The 1950s and 1960s saw a rapid expansion of international trade which depended on the development of efficient and reliable long-range systems of transport and communication and the rise of powerful transnational companies.

Within the graphic industries, designers found themselves in the front line in coping with this mass of printed matter. For the form of each document must be adapted to its use. In parallel with the development of international trade, an international graphic style emerged, to meet the needs of companies whose activities were not limited by frontiers of language or culture. The keywords here are rational, logical and effective. However, ‘local' graphic styles could still hold their own ; France was a case in point.

Air France (Caravelle) / Excoffon. Paris, 1964.

Gitanes / Morvan. Paris, 1960.

One of the foremost 20th century French graphic artists was Roger Excoffon. One example of his work is the highly evocative poster which he designed for Air France in 1964.

The 1950s and 1960s saw a rapid expansion of international trade which depended on the development of efficient and reliable long-range systems of transport and communication and the rise of powerful transnational companies.

Within the graphic industries, designers found themselves in the front line in coping with this mass of printed matter. For the form of each document must be adapted to its use. In parallel with the development of international trade, an international graphic style emerged, to meet the needs of companies whose activities were not limited by frontiers of language or culture. The keywords here are rational, logical and effective. However, ‘local' graphic styles could still hold their own ; France was a case in point.

Air France (Caravelle) / Excoffon. Paris, 1964.

Gitanes / Morvan. Paris, 1960.

The museum for English-speaking visitors

The museum for English-speaking visitors